All photos courtesy of Marc Pokempner

Before there were clubs like Kingston Mines, B.L.U.E.S. Rosa’s Lounge, and Buddy Guy’s Legends, there were joints like Theresa’s where the granddaddies of blues played regularly and helped define Chicago as the blues capital of the world. From the end of World War II and into the 1950s, rural blacks from the Delta Region of Northwestern Mississippi descended upon Chi-town in search of work in the city’s burgeoning, blue-collar industries. Life wasn’t much easier in Chicago than it was in the sharecropping fields of Mississippi, which led many young musicians to adapt Delta Blues into an urban form of music that reflected their angst. As a result, a series of bars opened up on the South Side, showcasing this new music most every night of the week. One such establishment was Theresa’s Lounge, which just happened to be one of the best of ’em thanks to the efforts of taverness extraordinaire, Theresa Needham. Her style and regular bookings of blues legends Junior Wells and a young Buddy Guy himself made Theresa’s one of the best places to see the blues since the day it opened. While the space lies abandoned in a non-descript building on the South Side today, the legacy remains.

Before there were clubs like Kingston Mines, B.L.U.E.S. Rosa’s Lounge, and Buddy Guy’s Legends, there were joints like Theresa’s where the granddaddies of blues played regularly and helped define Chicago as the blues capital of the world. From the end of World War II and into the 1950s, rural blacks from the Delta Region of Northwestern Mississippi descended upon Chi-town in search of work in the city’s burgeoning, blue-collar industries. Life wasn’t much easier in Chicago than it was in the sharecropping fields of Mississippi, which led many young musicians to adapt Delta Blues into an urban form of music that reflected their angst. As a result, a series of bars opened up on the South Side, showcasing this new music most every night of the week. One such establishment was Theresa’s Lounge, which just happened to be one of the best of ’em thanks to the efforts of taverness extraordinaire, Theresa Needham. Her style and regular bookings of blues legends Junior Wells and a young Buddy Guy himself made Theresa’s one of the best places to see the blues since the day it opened. While the space lies abandoned in a non-descript building on the South Side today, the legacy remains.

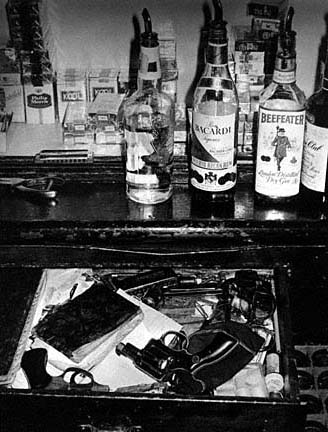

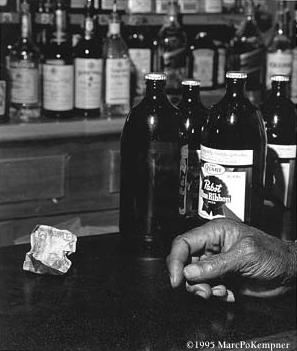

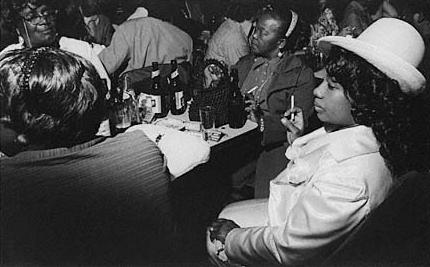

Theresa McLaurin Needham, a soft-spoken woman, opened up her smallish tavern in December 1949 within the tight confines of a basement in a yellow-brick apartment building. A modest sign that hung upon chain link fencing at street level modestly advertised the house band and nights of the week the bar was open. Cement steps led down to Theresa’s subterranean hovel. Inside, the place is described as “wonderfully funky and friendly,” “slightly dangerous,” and as having “unreliable plumbing.” A long wooden bar served an assortment of beer while liquor signs promoted booze that Theresa’s either never carried or no longer had. Behind the bar hung Christmas lights all year round and if your gun happened to slip out of your pocket the night before, you’d be likely to find it in the Lost & Found at Theresa’s the next night. According to Marc Pokempner, a photojournalist who spent a fair bit of time in Theresa’s taking pictures of both musicians and patrons (several of which are posted on this very page), described the scene in this way: “regulars came just about every night and they treated the place like their living room. They’d be drinking, singing, and having a good time in a way that none of my parents’ friends ever did.” Theresa’s attracted a predominantly black, middle-aged, working class crowd from the surrounding ghetto neighborhood, but its appeal reached global proportions as time wore on and more and more people became aware of the caliber of music offered nightly at Theresa’s.

Theresa McLaurin Needham, a soft-spoken woman, opened up her smallish tavern in December 1949 within the tight confines of a basement in a yellow-brick apartment building. A modest sign that hung upon chain link fencing at street level modestly advertised the house band and nights of the week the bar was open. Cement steps led down to Theresa’s subterranean hovel. Inside, the place is described as “wonderfully funky and friendly,” “slightly dangerous,” and as having “unreliable plumbing.” A long wooden bar served an assortment of beer while liquor signs promoted booze that Theresa’s either never carried or no longer had. Behind the bar hung Christmas lights all year round and if your gun happened to slip out of your pocket the night before, you’d be likely to find it in the Lost & Found at Theresa’s the next night. According to Marc Pokempner, a photojournalist who spent a fair bit of time in Theresa’s taking pictures of both musicians and patrons (several of which are posted on this very page), described the scene in this way: “regulars came just about every night and they treated the place like their living room. They’d be drinking, singing, and having a good time in a way that none of my parents’ friends ever did.” Theresa’s attracted a predominantly black, middle-aged, working class crowd from the surrounding ghetto neighborhood, but its appeal reached global proportions as time wore on and more and more people became aware of the caliber of music offered nightly at Theresa’s.

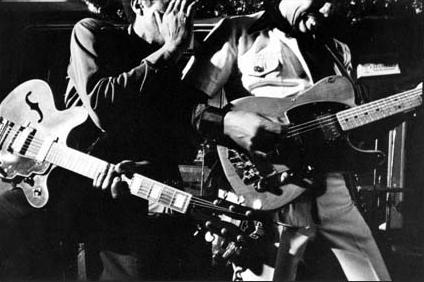

Also known as Theresa’s Tavern and T’s Basement, the joint featured “Live Entertainment” from Friday through Monday and featured Junior Wells as leader of the house band. This gig helped establish Wells as a top-notch blue musician and the club itself as a rival to other notable establishments also named after their owners, such as Pepper’s, Queen Bee, Sylvio’s, and Ross & Ma Bea’s. According to Delmark Records, the experience also led Wells to record On Tap, “an album that would emphasize Junior’s Theresa’s side, especially the uniquely creative musical partnership between Junior and Sammy Lawhorn.” Wells was later joined by bluesman Byther Smith, as well as local and touring bands, including Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Otis Rush, Earl Hooker, Otis Spann, Jimmy Rogers, and Howlin’ Wolf when he wasn’t playing at Big Duke’s Blue Flame Lounge. All of these musicians, most of whom came from in or around the Mississippi Delta, combined to create the “Chicago Style” of blues, which took the Delta Blues and added an amplified, rough-and-tumble edge to it.

Also known as Theresa’s Tavern and T’s Basement, the joint featured “Live Entertainment” from Friday through Monday and featured Junior Wells as leader of the house band. This gig helped establish Wells as a top-notch blue musician and the club itself as a rival to other notable establishments also named after their owners, such as Pepper’s, Queen Bee, Sylvio’s, and Ross & Ma Bea’s. According to Delmark Records, the experience also led Wells to record On Tap, “an album that would emphasize Junior’s Theresa’s side, especially the uniquely creative musical partnership between Junior and Sammy Lawhorn.” Wells was later joined by bluesman Byther Smith, as well as local and touring bands, including Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Otis Rush, Earl Hooker, Otis Spann, Jimmy Rogers, and Howlin’ Wolf when he wasn’t playing at Big Duke’s Blue Flame Lounge. All of these musicians, most of whom came from in or around the Mississippi Delta, combined to create the “Chicago Style” of blues, which took the Delta Blues and added an amplified, rough-and-tumble edge to it.

Some other bars in the area played up to the popularity of Theresa’s by hosting such musicians as “Muddy Waters, Jr.,” “BB King, Jr.,” and “Howlin’ Wolf, Jr.,” whose names were shamelessly listed on the bill to attract a crowd (some of whom though were apparently pretty damned good). According to Jory Graham in her book, Chicago, an Extraordinary Guide (1967), “Buddy Guy, an auto mechanic by day, a self-taught musician (who pulled wires from a window screen to make his first guitar), is, by general consensus, the finest blues guitarist in the city, if not in the jazz world… plays lead guitar for Junior Wells and also sings.” Also popular were “Blue Mondays” at Theresa’s where the city’s most popular bluesmen would come and… listen (and drink), while Junior Wells and his house band played. Such were the gritty, garish, good-time, working-class Chicago blues days of the 1960’s, and all this was available for a cover charge of not more than $2.

“Theresa’s Tavern, 4801 South Indiana, is a basement spot where you’ll hear Buddy Guy and Junior Wells after 10 PM, when they’re not booked out by the State Department for overseas tours. Buddy Guy, an auto mechanic by day, a self-taught musician (who pulled wires from a window screen to make his first guitar), is, by general consensus, the finest blues guitarist in the city, if not in the jazz world. He plays lead guitar for Junior Wells and also sings. The biggest night here is Monday, when every musician in town who can make it sits in.”

–Chicago, an Extraordinary Guide (1967) by Jory Graham

“For years Theresa Needham, 72 years old, the proprietor of a blues bar in a basement, has gone to City Hall every six months to obtain a liquor license. When she made the trip at the end of October, she was told her landlord had reported she had no lease. Without a lease, which she has not had since the 1970s, she could not obtain a license. The landlord since 1980, William Walls Jr., calls it progress. Mrs. Needham, a jolly woman known to many as ‘Miss T,’ calls it ‘lowdown.’ Need for Profit vs. a Handshake Agreement.

“[the landlord’s] goal is to bring the building into line with the housing code so his tenants can qualify for Government subsidies. Then he says he plans to raise rents to $641 a month from $325. The basement might then become a laundry room. ‘I have to make a choice. In order for me to continue on, I have to get a loan and I have to move Mrs. Needham. I’m not trying to be a bad guy. I’m not trying to hurt Mrs. Needham. But charity begins at home.’ Mrs. Needham has been denied a license to keep Teresa’s open because she does not have a lease. City officials have urged Mrs. Needham’s friends to begin seeking another location while the case is pending. Many fans are angry at the idea. One of them, Richard Brenne, said, ‘Asking Theresa’s to relocate is like asking the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to relocate or asking the Pope to leave the Vatican.'”

– excerpt from “Blues May Fade from Chicago Bar” by R. Shipp in the New York Times (November 29, 1983)

As the South Side steel mills started to shut down in the 1980s, so did Theresa’s. After an impressive run of 33 years, Theresa’s first moved her blues headquarters from its original South Indiana Avenue location in 1983 after the landlord refused to renew her lease (ala Lounge Ax), but then shut her doors for good less than three years later. She died in 1992. In recognition of her long tenure as a blues club pioneer, Theresa Needham became only one of two non-performers elected into the prestigious Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame in 2001.

As the South Side steel mills started to shut down in the 1980s, so did Theresa’s. After an impressive run of 33 years, Theresa’s first moved her blues headquarters from its original South Indiana Avenue location in 1983 after the landlord refused to renew her lease (ala Lounge Ax), but then shut her doors for good less than three years later. She died in 1992. In recognition of her long tenure as a blues club pioneer, Theresa Needham became only one of two non-performers elected into the prestigious Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame in 2001.

Even though both Theresa and her namesake bar are no longer with us, blues fans can find consolation in the fact that many seriously cool blues clubs remain where talent and style are welcome and musicians are part of the family – just like at Theresa’s. Among them, Buddy Guy’s Legends (South Loop), Rosa’s Lounge (West Side), BLUES (North Side) and Lee’s Unleaded Blues (South Side) stand out amongst the more popular tourist trap-type blues joints of which there are many. Even Smoke Daddy is worth a go for some blues and barbeque. It must be said that “tourist trap” is used here to designate characteristics of being widely advertised, and thus popular with out-of-towners, and far from cheap, so that all the promotions can be paid for. It is true that some of these places are quite good, like Kingston Mines and Blue Chicago (Ohio and Clark Street locations), but your visit will be crowded and expensive unless you go early in the week. For those less adventurous, you can listen to, “Blues for Theresa,” a song played by the Blue Lightening Band and available on their website, of which their member, Steve Dietzell, used to play in the house band at Theresa’s in the 70s and 80s. For more information and some excellent photographs of the bar, be sure to check the book Down at Theresa’s… Chicago Blues, with photographs by Marc Pokempner and writing by Wolfgang Schorlau. Here’s to you Theresa, hmm daddy…

“As of this writing, anyone of any color is welcome at the Negro blues shrines. The audiences are mainly Negro, of course; the atmosphere can be very mixed, but it’s always loose and easy; and soul—the raw emotion, the pain of being black—is not withheld. People stomp and shimmy in their seats and call out to the singer. And if Buddy Guy says to the crowd at Theresa’s, as he did one night, ‘People, hold on to me’ and begins to sing ‘I’m hurtin’,’ and halfway through his song, begins to cry, the audience will be crying too. It’s like Robert Anson said, ‘Blues is the anthem of the working class, the unemployed, the hustlers, and there’s no attempt to deny the obvious misery of being a Negro. [The shrines] are places of honesty personified.’ So it’s where you go to hear and begin to understand through the blues your fellowman.”

– Chicago, an Extraordinary Guide (1967) by Jory Graham

“Theresa’s is a basement on South Indiana Avenue. It’s a low-ceilinged place with exposed water pipes wrapped in what looks like ancient Christmas tinsel from a season long forgotten. Theresa’s is also an institution known by blues devotees worldwide.”

– excerpt from Herb Nolan’s Chicago Tribune article “A Blues Man Hits a Few High Notes”

(November 21, 1976)

“Not the greatest neighborhood in the world [48th and Indiana] — nor on the South Side, for that matter — but on the inside, everything is so fine, especially the music, which is Chicago-style blues. Don’t go expecting the big, TV-tossed names. The recent lineup has included such performers as Sammy Lawhorn, Nate Apple White, Muddy Waters Jr., Mary Lane, and Ernest Johnson.”

– excerpt from Clifford Terry’s Chicago Tribune article “101 Good Things About Chicago” (March 10, 1978)

Theresa Needham

(1912 – 1992)

“For awhile, as a young graduate student in Hyde Park, I began to go to Theresa’s. I was there on a few ‘bad’ nights, where the music never clicked. Most of the time, however, the blues found a deep groove that was simply astonishing. And the place was always a scene.

“One night, when it was time to leave, I walked out to my car only to find there was a crowd next to it, and a fight happening on the street. I wasn’t about to ask everyone politely to move the fight so I could get out, so I stood at a distance and waited. Soon, Junior Wells strutted (yes, truly strutted) out of Theresa’s where he had been holding court behind the bar, in his trademark furry hat, and on the strength of his authority alone, terminated the fight and dispersed the crowd.

“On another night, there was a table of food, and while a friend and I sat at the bar, people kept bringing over plates of food to us. I asked one patron about the occasion, and she said it was Robert’s birthday. I asked who was Robert, and she indicated a fellow sitting right in front of the stage, facing the musicians, surrounded by friends. I went up to him and tapped him on the shoulder; he turned, and I asked, over the loud music, ‘Are you Robert?’ He looked over at me suspiciously, and said, ‘Who wants to know?’ (I was one of two white people in the place.) I asked again, and he again asked who I was. Finally, I said, ‘If you are Robert, happy birthday!’ His demeanor shifted, he took my hand, and shouted a warm thanks.

“Perhaps on another night, I took the only empty seat I saw, opposite a man who had apparently passed out at the table. After awhile he raised his head, looked at me, and said, ‘Are you Jewish?’ (though in rather slurred speech). I wasn’t sure if I heard him correctly, and asked him to repeat it. ‘Are you Jewish?’ I answered yes, and asked why. He said, ‘Most nice folks are either black or Jewish,’ put his head down, and passed out again.

“Thanks for the website.”

– P.F. (May 2, 2005)

Indiana Manor

Former location of Theresa’s Lounge (basement, bottom right)

Now for sale